Doc. Dr Darius Linartas

Architect, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University

Competitions, acting as indicators of an individual type of cultural production, show a hyperbolised picture of the situation (Lipstadt, 2003). Keeping in mind the architectural integrity and analysing the narrow aspect of creative competitions, can reveal much wider tendencies. The same could be said on the competitions held in the Soviet era. The spectre of the creative competitions of that time shows not only the architectural peculiarities of the day, but also its general cultural, economic, political and social situation, as well as the changes, priorities or attempts to create an image of certain aspirations.

Architectural competitions were very popular during the independent Interwar Lithuania with approximately 40 of them held in a short two-decade period (1918-1940) (Kančienė, 1996), while during the Soviet era the average number of competitions didn’t even get close to the pre-war level. However, the small number of competitions and their low results, as well as poor written resources don’t mean that their influence to the architectural development and creativity of the architects of that time was small as well. That is most likely only another of the peculiarities of the Soviet era.

A lack of competitions was especially notable in the early years. Due to the war and the post-war situation, Lithuania had lost almost all of its creative potential (Nekrošius, 2007). Lack of staff led to architects coming to Lithuania from Russia (mostly from Leningrad). That’s why in the first years after the war Lithuania, just like the Soviet Union, was predominated by “imported” retrospective Stalinist architecture (Mačiulis, 2002). Thus, there was no internal competition between designers, resulting in no natural need for competitions. The rare competitions that did take place, however, were initiated by local authorities or that of the Soviet Union.

Probably the first Soviet tender was announced half a year after the end of the World War II. At that time the State Committee for Construction of the USSR organised several closed architectural competitions. Their goal was to collect general project suggestions for the central parts of capital cities in countries that were particularly damaged during the war. One of them was dedicated to find the solution for the urban rearrangement of Lukiškių Square in Vilnius and surrounding territories. For this purpose it was planned to prepare six commission projects. Two projects were supposed to be submitted by architects from Moscow, Leningrad and Lithuania each. Moscow was represented by the teams of the architects A. Velikanov, N. Shelomov and I. Sobolev, Leningrad – S. A. Gegello, A. Baruchev and J. Rubanchik, while Lithuania – K. Šešelgis, V. Zubovas and V. Mikučianis. The tender participants were given a task of arranging the main city square and the complex of governmental buildings in the territory of Lukiškių Square by including Tauras Hill and the surrounding neighbourhoods into the project (Mikučianis, 1997). Based on the projects submitted for the tender, the commission selected V. Mikučianis’ project for further development (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Competition project for Lukiškių Square (architect V. Mikučianis, 1945)

Also, it was advised to consider the project solutions, submitted by the architects V. Zubovas and K. Šešelgis. Later V. Mikučianis, one of the tender participants, wrote: “… it turned out so that under the dictate of the high state and Moscow’s authorities only a small part of my ideas for the project were implemented …” (1997).

In spite of that, Lukiškių Square remained a rather popular object for architectural competitions. K. Šešelgis described six designing initiatives in this territory in the Soviet era alone. Even four of them more or less looked like competitions. The majority of cases involved using the square for new buildings, but neither of these tender offers were implemented. “… No other urban complex (square, neighbourhoods, public buildings, etc.) in Lithuania was ever a subject of so many design and project options …” (Šešelgis, 1997).

Talking of urban development, there were even more of these competitions in the Soviet era:

– Closed tender, inviting offers from all over the Soviet Union, for Vilnius city centre in 1964 between groups from design institutes of Vilnius, Leningrad, Minsk and Riga (Cibas, 1964). The 1st prize was not awarded. The 2nd prize was awarded to A. Nasvytis, V. Brėdikis and V. E. Čekanauskas, A. A. Jakučiūnas;

– A tender for the preliminary project of Žalgiris residential neighbourhood in Vilnius city in 1974 (Girčys, 1975);

– A tender for the preliminary project of the southern part of Šeškinė residential neighbourhood in Vilnius city in 1975 (Girčys, 1976);

– A closed tender of Kaunas Department of Urban Development Planning Institute for the central part of Smėliai residential neighbourhood in Kaunas in 1976 (Baršauskas, 1976);

– Tender for Pašilaičiai residential neighbourhood in 1978 (Balėnas, 1978).

A significant share of this type of competitions shows the large construction scale of new residential neighbourhoods and public centres in the major Lithuanian cities. No private property created an opportunity to use one idea or a project to build huge urban complexes. However, new neighbourhoods were not built according to the ideas generated for these competitions. Only a part of the urban solutions for the detailed plan of Vilnius city centre were actually implemented, e.g. “the urban hill” (Mačiulis, 2002). There are also numerous contradictions between the goals declared during the tender and the works that had actually won them. E.g. the participants of the tender for Žalgiris (currently Šnipiškės) neighbourhood were asked to offer exceptional compositions and spatial solutions, which would create an appropriate background for the city centre. However, the most favoured ideas were those that met the criteria of industrial construction methods, maximum housing density and economy. Naturally, the project acknowledged as the best, wasn’t much different from a typical mass-construction residential neighbourhood of that time (Fig. 2). What is interesting, is that despite the immensely pragmatic assessment criteria, the tender participants of that time didn’t avoid complex or even futuristic suggestions, such as replacement and deepening of transport routes, or even moving sidewalks.

Fig. 2 The winner of the first prize for the design of Žalgiris (Šnipiškės) residential neighbourhood in Vilnius, designed by the architect Z. Daunoravičius, 1975.

In the mid. seventies the Soviet Union abandoned decorous architectural pomp and radically changed the ideological-aesthetic architectural programme. That was influenced by the end of Stalinism and the course of creating an image of democracy. Architectural style came closer to the global architectural aesthetics. Lithuanian architects were among the first in the Soviet Union to start working according to the ideologically new methodology, also known as the Soviet modernism (Nekrošius, 2007). Here came the new generation of architects – graduates from faculties of architecture at Kaunas Polytechnic Institute and Vilnius Institute of Art – N. Bučiūtė, G. Baravykas, A. Nasvytis, V. E. Čekanauskas, V. Brėdikis, etc. (Mačiulis, 2002).

Probably the best example of this creative shift is the closed tender for Vilnius Opera and Ballet Theatre, which took place in 1958 between the architect A. Spelskis, representing the older generation and his young colleague N. Bučiūtė. The commencement of the complex process of changing essential architectural concepts determined that the competition between the two architects was won by Nijolė Bučiūtė’s project, which looked very innovative and original at that time (Fig. 3). She was entrusted with the further design of the theatre, which had undergone slight changes and was implemented in 1974 (Mikučianis, 1997).

Fig. 3 Vilnius Opera and Ballet Theatre – interior sketch and the actual implemented project (architect N. Bučiūtė)

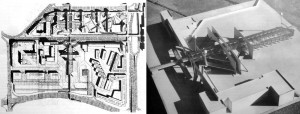

Even at the specific situation of that time competitions helped numerous architects reach their professional heights. The open creative tender, held in 1966, was won by young architects G. Baravykas, P. Adomaitis, V. Vielius and R. Pranaitis (Fig. 4). The same authors worked on its implementation. Discussing that situation in his monograph, R. Buivydas noted: “Perhaps this was namely why it is so easy to characterise this piece as probably the most notable of our creations, a symbiosis between intellectually focused complexity and, at the same time, simplicity …” (Buivydas, 2000).

Fig. 4 Museum of Revolution in Vilnius (currently National Gallery). Tender model (architects G. Baravykas, P. Adomaitis, V. Vielius and R. Pranaitis)

Competitions also contributed to the formation of the well-known creative duo of the architects Saulius Šarkinas and Leonidas Merkinas. Tired of standard projects, L. Merkinas offered his younger colleague to participate at the tender for the Youth Centre in Vilnius, located in the modern-day Sereikiškės Park, which took place in 1977: “… at least there will be no one to build boundaries and wave norms or rules at our faces …” (Vaitys, 2007). Their project (Fig. 5) was acknowledged as the second and became the beginning of the long joint creative path of both of the tender participants. Numerous competitions and prize-winners feature the names of the architects Algimantas and Vytautas Nasvyčiai (Petrulis, 2007).

Fig. 5 Competition project for the Youth Centre in Vilnius (1977, architects S. Šarkinas and L. Merkinas, 2nd prize)

Just like everything in the Soviet era, architecture and architectural competitions were ruled by the principles of planned economy, general regulations and control. Numerous creative, yet ideologically “useless” objects were discarded to the category of “dead” projects, i.e. were never implemented. This category was oftentimes supplemented by tender projects. The open competition for the plan and buildings of Kaunas Bus Station, held in 1978, was won by the architects A. Alekna, G. Telksnys and L. Vaitys (Fig. 6). Their project received numerous repercussions in public and was referred to as a rather successful example of post-modernism that managed to reach Lithuanian architecture through the “iron curtain”. Unfortunately, their ideas were never implemented. In his article A. Vyšniūnas made an ironic note: “… However, I think that it’s for the best that the project for Kaunas Bus Station was never implemented. The cultural level of constructions in the late 1970s did not deserve such a project. …” (1997).

Fig. 6 Competition project for Kaunas Bus Station (architects A. Alekna, G. Telksnys, L. Vaitys, 1978)

The poor possibilities to implement tender ideas is also illustrated by the list of works of the architects S. Šarkinas and L. Merkinas – constant participants and prize-winners of various creative competitions. In the 12 years of work in the Soviet era alone (1977-1989) they participated at 8 competitions, won 3 first prizes and 4 honorary certificates. Not a single project-winner was ever implemented, even with all the necessary design documents ready (Vaitys, 2007). Thus, we could say that the history of competitions in the Soviet Lithuania has a much deeper and valuable layer of “dead” projects than implemented ones and the majority (even significant) urban and architectural solutions of that time were implemented without any tender.

Competitions for monuments were slightly more dynamic and liberal than urban and architectural competitions in the Soviet days. It should be noted that namely this type of competitions, also participated by architects, was the first to became public and marked significant changes in creative art. The tender regarding the monument for the victims of Pirčiupis took place in 1958 (1st prize – architects V. E. Čekanauskas, V. Brėdikis); monument for the victims of fascism in Paneriai – 1961 (implemented only in 1984, architect J. Makariūnas); monument for underground activists that died in Kaunas – 1965 (1st prize – architects G. Baravykas, V. Vielius, sculptor S. Šarapovas; implemented in 1975-1979), four stages of the tender regarding the memorial complex of the 9th fort in Kaunas – 1968-1970 (1st prize – architects G. Baravykas, V. Vielius, sculptor A. Ambraziūnas; implemented in 1975-1983, Fig. 7). These monument competitions marked the transition from the aesthetic norms of social realism, protected by the state during the days of Stalin, to abstract canons of modernist aesthetics (Buivydas, 2000).

Fig. 7 Preliminary model of the memorial of the 9th fort (architects G. Baravykas, V. Vielius, sculptor A. Ambraziūnas)

Compared to architectural competitions, the number of Soviet monuments actually implemented exceeds that of architectural objects. In a sense this shows the type of ideological and propaganda-related priorities, characteristic of the time, involving implementing projects that require fewer capital resources, but offer a greater political effect. In other words, the ideological idea of the project used to ensure smoother funding and implementation.

The integrity of the political regime and other public processes (including architecture) leaves no doubt. A project tender is a democratic selection of an architectural idea. It is only natural, that quantitative and qualitative shifts in the global history of project competitions used to match the rise of democracy in the society, e.g. in ancient Rome, Greece, Renaissance (Haan, Haagsma, 1987). Therefore, the practice of architectural competitions could indicate the “health” of certain public and political processes in certain times and places, at the same time making certain architectural assumptions.

Seeking to meet the criteria of its declared values, the fictitious Soviet democracy had to organise not only political, but also creative elections – competitions. However, the small number of competitions and tender projects actually implemented, compared to the scale of construction, shows that in most cases the architectural quality was not a priority. The only exception was the objects that were important from political and ideological perspective. This could be illustrated by the purpose of the tender projects implemented – the Museum of Revolution, the Palace of the Supreme Soviet and Soviet monuments. The works that were not as ideologically significant used to keep adding to the category of the “dead” projects.

Lithuanian architects that had actively participated at the architectural processes in the Soviet era, say that Lithuanian continued the traditions of the pre-war school, with a hint of Western and Central European influence on the post-war Lithuanian urban development (Devinduonis, 1998) and architecture (Buivydas, 2006). Nevertheless, they often emphasize that the foreign architectural tendencies used to reach the designers of that time in fragments and formal forms. The projects of that time were also inevitably influenced by the directives of the USSR (as a part of the general policy of the Soviet architecture). These processes reflected on project competitions as well.

In the Soviet Union, which was based on constant reporting, it could have been as one of the motives for organising competitions. A report for the authorities could feature not only an implemented object, but the mere fact of a tender taking place. This demonstrative scenario could at least partially explain the history of numerous competitions for Lukiškių Square, which brought no tangible results, except for the paving and building a monument for Lenin in 1952. Thus, it was decided to avoid more complex general urban solutions and implement the part that is the most efficient in terms of propaganda – … forming a giant axis from Tauras Hill and the Chamber of Trade Unions to the square, featuring the “founder” of the absolute Soviet dictate …” (Grunskis, 2007). Based on these examples, we could assume that competitions used to involve projects that were complex, slow or didn’t require much funding in order to create an impression of action, rather than finding and implementing a fast solution. The representative and fictitious purpose of such events is also illustrated by the fact that most of these competitions revolved around the capital or Kaunas.

The organisers of Soviet creative competitions felt no responsibility or obligations to the participants of the tender neither in terms of authorship, nor project implementation. They used to save construction materials and working hours, but didn’t appreciate the intellectual and creative work. Competitions used to be held without a clear planning task under unspecified or ambiguous conditions. This circumstance became even clearer during the first years of independence and the attempts to adapt the imperfect model of Soviet competitions for the conditions of developing free market (Čaikauskas, 1999).

In the Soviet Lithuania competitions were merely a part of the administrative order and couldn’t grow as a member of free market competition. Planning Institutes had strictly divided and monopolised areas of activity. The Institute of Planning Public Economy (Komprojektas) specialised in the field of reconstructions, the old town was monopolised by the Monument Restoration and Planning Institute, the Institute of Collective Farm Planning used to design all objects in the province, while the Institute of Urban Development Planning used to take all of the remaining “atypical” objects. Essentially, this encouraged closed competitions at individual planning institutes. An employee of a “wrong” institute participating at a public state-wide tender would become a problem. What made this division even worse was the lack of information distribution. Announcements about a new tender used to be advertised only in the stairway of the Architect Union or the corridors of some planning institute (Čaikauskas, 1999). If it was a holiday time or if the tender revolved around another city, news of a new tender would reach only a limited number of architects.

Even those few competitions that did take place were far from standard. In many cases the object was designed without any regard to the results of the competitions that had already taken place. Namely that’s how the tender for the State House of Political Education (currently the Congress Palace) in Vilnius took place in 1979. Neither of the participants was granted the first prize and the right to design the object. In 1984, with no separate tender, the order went straight to the 2nd department of the Institute of Urban Development Planning, which was the monopoly of “unusual” buildings in the country. At first the project was assigned to the architect V. Čekanauskas (who didn’t even participate at the tender of 1979), but, looking for better results, was reassigned to his more productive colleague E. Stasiulis, who implemented this project (Mačiulis, 2003). The story of the Chamber of the Council of Ministers went down a similar path. Thus, in cases when the state order was specific and clear, a tender would actually become an obstacle. In this case the right to design the project used to be entrusted with someone already “tested” or the state planning institute, which used to assign an architect from the inside. This shows that planned economy had bred an inclination towards predictable results in architecture as well. Competitions, being an area of free competition, contradicted this notion.

In spite of all the shortcomings in the competitions of that time, the architects that participated at them highlight the significance of the process of competing itself. For example, the monograph about the architect G. J. Telksnys refers to preparing a tender project as “an additional load – work that you do after work. And despite the endless fatigue and sleepless nights that would last for months … that was the most creative and refreshing time of ideas and dreams” (Vaitys, 2005). Based on the memories of the contemporaries, we could list the major motifs for participating at these competitions in the Soviet times. One of them was the opportunity to get away from the daily routine, Soviet norms, primitive technology and ideological control (Vaitys, 2007). Analysing the works of constant participants S. Šarkinas and L. Merkinas, L. Vaitys also notices their professional improvement and the ability to solve tasks, posed by increasingly complex circumstances, a notably increasing mastery and a resolution to take up the most complex projects: “… you were really lucky to be “schooled” that way in the Soviet era …” (Vaitys, 2007). Aside from the opportunity to draw the perspective for objects that were technically difficult and, we could even say, futuristic in the Soviet conditions, tender participants had more freedom to take up complex tasks and create architecture of new quality. Local competitions were the driving force, which helped to escape the primitive daily routine and strive for professional heights under limited conditions, while rarer international competitions enabled to take a look at yourself from different perspectives of foreign colleagues and check if we weren’t actually lagging behind the rest of the creators of the world (Vaitys, 2007). Despite the lack of productivity and organisational weaknesses in the Soviet competitions, we could conclude that in some sense they became the ground for building the vision of our modern-day architecture and raising the professionals that can implement it.

Literature

Balėnas, K. 1978. Konkursui pasibaigus, Statyba ir architektūra 3/226: 8–10.

Baršauskas, J. 1976. Po konkurso gyvenamajam rajonui suprojektuoti, Statyba ir architektūra 12/211: 9–10.

Buivydas, R. 2000. Gediminas Baravykas. Kūrybos pulsas. Vilnius: Archiforma.

Buivydas, R. 2006. Architektūra: pozityviai ir negatyviai. Vilnius: Ex Arte. 224 p.

Cibas, A. 1964. Kaip atrodys ateityje Vilniaus miesto centras, Statyba ir architektūra 64/11: 18–25.

Čaikauskas, G. 1999. Konkursas – susibėgimas ar susidūrimas?, Archiforma 99/3: 95–96.

Devinduonis, R. 1998. Lietuvos ir Vakarų Europos regioninio ir miestų planavimo praktikos paralelės, Archiforma 98/1: 88–98.

Girčys, G. 1975. Mintys apie būsimąjį „Žalgirio rajoną“, Statyba ir architektūra 2/189: 4–7.

Girčys, G. 1976. Šeškinės rajono pietinės dalies išplanavimo konkursui pasibaigus, Statyba ir architektūra 7/206: 11–13.

Grunskis, T. 2007. Diktato architektūra (I). Lukiškių aikštė, Archiforma 07/1: 104–105.

Haan, H. D.; Haagsma, I. 1987. Architects in Competition: International Architectural Competitions of the Last 200 Years. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. 220 p.

Kančienė, J. 1996. Lietuvos architektų orientyrai tarpukaryje, Archiforma 96/1: 55–59.

Lipstadt, H. 2003. Can ‘art professions’ be Bourdieuean fields of cultural production? The case of the architecture competition, Cultural Studies 17 (3/4): 390–418.

Mačiulis, A. 2002. Lietuvos architektai. Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, Lietuvos architektų sąjunga. 647 p.

Mačiulis, A. 2003. Edmundas Pranciškus Stasiulis, Archiforma 03/1: 42–48.

Mikučianis, V. 1997. Atsiminimai apie pokarinio Vilniaus konkursus, Archiforma 97/3: 74–80.

Nekrošius, L. 2007. Idėjų paralelės: struktūralizmas, APS 2007 m.: 30–37.

Petrulis, V. 2007. Algimantas ir Vytautas Nasvyčiai: dvi asmenybės – viena architektūra, Archiforma 07/1: 50–59.

Šešelgis, K. 1997. Vilniaus Lukiškių aikštės formavimo projektai, Urbanistika ir architektūra t. 24 (2): 32–53.

Vaitys, L. 2005. Gintautas Juozas Telksnys. Architektas. Vilnius: Dailininkų sąjungos leidykla „Artseria“. 143 p.

Vaitys, L. 2007. Saulius Šarkinas. Architektas. Vilnius: Dailininkų sąjungos leidykla „Artseria“. 112.

Vyšniūnas, A. 1997. Mirę projektai: Autobusų stotis. Kaunas, Archiforma 97/3: 104–106.

Žickis, A. 1996. Architektūros projektų konkursai, Archiforma 96/2: 86–88.