Text author Lukas Šiupšinskas

Changes in Public Spaces of the City

A city is a cradle of a civilized community, its beginning and at the same time its product. Public space of the city is a platform, on which existing local social aspects and local history narratives are present and ready for reading. Art in these spaces, most frequently sculpture, has been performing a role of a cultural boundary mark since ancient times. The artworks, monuments, memorials standing in public spaces create an emotional background and explain a cultural character of the place. Still, at the time of substantial changes, when the cultural or social context of the period is reversed, a problem occurs as spaces and artworks create a dissonance between the place ant a particular time period. Such spaces even may become problematic points in the contemporary city, as they do not meet anymore the needs of the public and do not comply with requirements set by the particular period. Then, a question arises: what should be done with these objects and spaces? Should they be regenerated to meet new needs, respecting the former form, or be destroyed?

In the cultural landscape of the contemporary city, an increasing demand for public space regeneration has been felt. As social and cultural changes take place in post-soviet Lithuania’s public life, these processes are reflected in squares and sculptures of the cities, still they are delayed. In the public space of the city, several signs of former ideology, inconsistent with today’s situation, have remained so far, while in some places they have been replaced by persistent emptiness. In today’s context, a need occurs “to rework” such a public space as well as pieces of art in here. Sąjungos Square in the city of Kaunas is among examples of such type issues. This space does not find its new function or a form in the historical development of this place. The former Monument of Soviet times exists as an object disfiguring the face of the micro-district. I got interested in historical and cultural specificity of this place, wanted to understand potential reasons, causing dwindling of this spot. As my occupation is sculpture, I have set a task for myself to find a possibility, maybe a theoretical one, of regenerating this Square and check hypothesis, concerning sculpture participation in this process, for being an effective tool of humanizing the space.

According to the philosopher Leonidas Donskis, Lithuania is a phenomenon of delayed advancement of modernity. In the 20th century, the interwar period, synchronization with Western Europe’s modernity started, yet, was artificially disrupted for fifty years by Soviet occupation. “At present, during such a short period historically, Lithuania experiences great social and political stresses, which in Europe’s and American civilization processes had been distributed throughout much longer periods.” [1] This has influenced the overall specificity of public space development in all post-soviet countries after they entered the phase of democratic society development. Having in mind this idea as a starting point, I want to explain the motive, why I focus my attention on one public space, which is Sąjungos Square in Vilijampolė micro-district. Sąjungos Square in Vilijampolė is sort of indicator, providing specific information on these stresses and processes.

Boundary Marks of Art Development in Public Spaces

The concept of public spaces of the city formally means territories of people’s common usage in the city [2]: parks, riversides, squares, central squares and other territories of similar purpose. Such spaces are a qualitative indicator of the city, because this parameter shows the relationship between the local community and the city itself. A square in a city, agora, used to be the first central public space for people to gather and social institutions to act, or, in other words, a place for formation and representation of a collective identity. Art in public spaces, most frequently sculptures, provides people with reference points, which assist them in understanding their own place in urban surroundings, temporal space and culture. A human needs reference points so that he or she could feel comfortable in his or her everyday life. For example, agoraphobia is a situation when a person is afraid of open spaces, and this fear appears in the environment, where he or she does not perceive their own situation as they do not have any reference point or other signs guiding this person. Sculptures, artworks or other cultural boundary marks in the city shall act as the point, which are necessary in order to feel comfortable in person’s own environment. Mircea Eliade argues that “detection or identification of the centre is tantamount to creation of the World” [3].

From an historical perspective, since the very beginning of civilization, communities of people wanted to organize and create such structures like squares or monuments. People for different reasons “were seeking constantly to express their experiences through art” [4]. The oldest civilizations had already had a tradition of creating forms, consuming lots of human resources, physical efforts and craftmanship in order to “raise affection, a strong emotional response, and be able to organize and retain the field of emotional strength in the space” [5]. A demand for forms of new space occurs when generations, historical context or social background change.

A changing worldview creates new stories, new heroes and values, which in a long run are immortalized in public spaces and replace the destroyed old ones. The most striking examples are when sculptures and monuments, devoted to former political regimes, religious confessions are openly destroyed, i.e., when social cataclysms take place. Squares and their stories change brutally, depending on a new domineering power in the city. An illustrative example of such changes is a commemorative column in the Place Vendôme in Paris. This work, erected in 1810 as a memorial to Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, was demolished by “allied troops” in 1814. Later, after Napoleon III (1808–1873) came to power, the monument was restored and again demolished in 1871 to be finally restored in 1873 [6]. This Place and the Monument constantly confronted and changed alongside with the changing local political background. The practice of destruction of artworks, telling about historical events, goes back to Ancient Rome times, when a law was adopted, called damnatio memoriae (“condemnation of memory”). Under this law, statues, reliefs or inscriptions, created previously in memory of a person, who has been declared an enemy today, had to be destroyed.[7]

In the democratic world of new times in the West, there is a possibility for public space changes to take place in a civilized way through finding a different relationship with the place and its history. When democratic, liberal ideas of the public appear in the USA and Western Europe, possibilities emerge for public space to change in a more humanized way. Methods, respecting the past or making up with it, occur for finding the new measures of artistic expression, meeting the needs of the contemporary society.

Humanizing the Public Spaces of Cities in the USA, Western Europe and Lithuania in the Second Half of the 20th Century

Under conditions of democratization of city spaces and increase in involvement of residents into local cultural life and its processes, art in public spaces from the Seventh decade until our days has reached new quality heights. The sixth decade was the beginning of Western cultural revolution, which had been sensed in all spheres of culture and science. Philosophy, music, fine art, literature, theatre, architecture – all these and not only these spheres at that time entered a new phase, which allowed experimenting and creating new forms of self-expression.

Analysing the subject of relation between public spaces and contemporary art alongside with the literary sources devoted to this field of research, the modern art of the Seventh decade is frequently presented as an important historical breakthrough. Many art research papers when analysing public spaces refer to the period above in American and European cities. Why has this transitional period from modernism to post-modernism generated a new and unique generation of creators, which has left a deep imprint in the public space of the city?

Certainly, we cannot mystify one period or one sphere as absolute and exclusively positive. Italian author, philosopher and literary critic Umberto Eco in his book “The Open Work”, thinking about the problematics of the modernistic, avantgarde art, writes that “Art frequently tends to a negation-restoration discourse, accelerating the time and submitting visual documents of the process, which at other levels even has not begun” [8]. Having drawn attention to this, you need to look objectively at different interpretations of history and single out the essential events of a certain time period. To perceive that democratization, regeneration or social changes in a public space, changes in the relationship between an artistic work and a viewer are not absolutes of the given time that have been formed and entrenched in one day. They are processes, being developed at higher or slower speed and intertwining, and which have become characteristic trends of that period.

In 1963, in large cities of the United States, several programmes for public spaces began to function, such as “General Services Administration’s Art in Architecture” and “National Endowments for Art in Public Places”. These state programmes were initiated by public movements, consisting mostly of artists, and by initiatives drawing attention to the public spaces in the cities. In 1963, they achieved that a law was adopted in the United States, stipulating that one percent of state purpose building funds would be assigned to sponsor art [9]. These state programmes implemented financing of art works in the facades of state buildings and offices, interiors and public spaces created for residents of the cities.

Unfortunately, no similar art patronage practice is known in Lithuania, and no chances to have it in the nearest future. Tomas S. Butkus, writing about a public space in times of intersection of eras in Lithuania, states that “after another phase of development was entered in 1990 when Lithuania restored its independence, the new system in power took advantage of the “open door programme” (inevitable feature of transition), supported thoughtlessly the development of the free market and implemented capitalist relationships in all spheres of public life” [10]. This transitional period allowed appearance of very important objects in history of public space art of Lithuanian cities, which could not emerge before restoration of the Independence. To say the truth, some of these objects could not appear even today, because transitional period optimism and euphoria in art were replaced by the extremely inflexible culture administration structure.

Such objects like “Kablys” [The Hook] by Mindaugas Navakas (1994) installed on the façade of Railway Workers Chamber and artistic intervention by Gediminas Urbonas with soviet sculptures on the Green Bridge “Užmiršta dabartis” [The Forgotten Present] (1996) are perfect interventions and sculptural transformations of a place, the lack of which has been felt in the Lithuanian public space art in recent years. Transformation of Soviet monuments by artistic interventions appeared not only in Lithuania. In post-soviet countries, this practice is quite often applied. A tendency in art related to humanizing, neutralizing the monuments in public spaces, characteristic of Eastern Europe, emerges. This tendency seems increasingly abandoned in Lithuania, where it has been left exclusively at the level of discussions, speeches and evaluations.

No Man’s Land

“Sąjungos” Square in Kaunas is among the objects, which could be named a “no men’s land”. (see Fig. Fig. 1, 2, 3). “Sąjungos” Square is a space, formed in the centre of the historical Vilijampolė settlement. At present, this Square is a problematic public space of the city, not performing any quality function of a city square nor a micro-district square (see Fig. 4). In the territory of the Square, concrete ruins of the Soviet Monument lie, which do not create a quality space and occupies more than one third of the Square’s area. City’s public spaces are direct consequences of historical city narrative and activity of local people, “Sąjungos” Square is not an exception. If you look more closely to this abandoned concrete scar of the city of Kaunas, you understand that it performs a representative function of this place, still not the one, which would be liked by many. Not existing anymore Monument is able to tell a story as well, still, due to its regress it does not tell the things that have been created for by the authors of the Monument. A grotesque concrete shell of “Sąjungos” Square tells not the most pleasant story of this place, yet, a truthful one, this object is stating itself.

To a person, who does not know the history of this place, the first impression will be negative undoubtedly. There is no season, no lighting suitable, under which this place seems suitable to have a status of a city square. To speak about this square and analogues of similar places, a person first of all must grow up from the stage of denying, must not refer to the assumption that this place as if occurred from nowhere. Such an attitude forms a bad habit of waiting until the problems appeared from “nowhere”, someday will disappear to “somewhere”. Having refused such an attitude, one may start thinking about the future perspectives of this place. Not all societies, among them our society as well, has asked itself a question about how should these objects and spaces be handled? Again, a question arises, most frequently alongside a new public discussion, which (like a mantra) sounds as follows: regenerate them to meet new needs, respecting a former form, or destroy it?

Namely these issues attracted my attention and I got interested in this place. I have devoted my time to searching for possibilities of “Sąjungos” Square regeneration. When hunting for answers to the questions, which, in my opinion, had not been asked, I explored regeneration strategies applied abroad (see Fig. 5) and was digging into experiences of neighbouring countries concerning “reworking” of the Soviet sculptural heritage (see Fig. 6).

The “reworking” of the Soviet sculptural heritage, a process taking much effort in Lithuania with so many ineffective competitions of sculptors organized suggest an opinion that many are looking for design solutions and do not understand the problems. It is thought that if you create a “design” of a space in the urban designing sphere, you must understand that this is not an artistic process only, creation involves investigating the place and making decisions and this activity includes finding solutions to the problems [11]. The analysis of such a problematic object, while seeking to understand possibilities of regenerating the place or applying humanizing practices, shall not be possible without a wider knowledge of the local historical context.

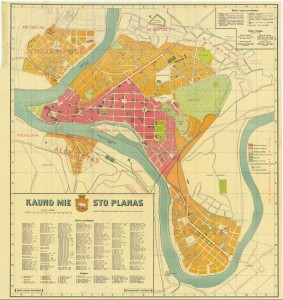

Old Slabada

Vilijampolė is part of the city of Kaunas. It is situated on the right banks of the rivers Neris and Nemunas, sitting near the confluence of those two. The word Vilijampolė is a combination of two words, Vilija and pole (people speaking Polish and Russian used to call the Neris by another name – the Vilija, while the Polish word pole means “a field”). Since the very beginning, Vilijampolė has had another name in slang – slabada, which in old times used to be a name of a small town free from serfdom; again, this word originates from the Polish word swoboda, which means freedom [12]. Interestingly, this slang term was used even in times of Vilijampolė establishment, in the 17th century, and has been very tenacious so far. Many call this district slabotke, and, most certainly, even do not question the origin of this term. Vilijampolė, as part of the city of Kaunas, exists from 1919 (see Fig. 7). The settlement was founded in 1652 [13] as an independent town, which alongside the other suburbs of Kaunas was connected to the city of Kaunas in the first half of the 20th century. Chronologically, the history of this place could be divided into two separate parts: Vilijampolė – an independent settlement and Vilijampolė – part of the city of Kaunas.

Historically, even in 1000 BC, at the Northern foot of Veršvai hillfort, a settlement existed. In 1363, after the crusaders destroyed Kaunas castle, Lithuanians rushed to build a new castle, which was named New Kaunas. It is thought that this one stood in Veršvai village, current Lampėdžiai, Vilijampolė eldership [14]. The lower Nemunas – Neris terrace, which today is occupied by Vilijampolė, was almost not developed until the 17th mid-century. In the 17th century namely, the territory started to be populated and this fact laid the foundations for occurrence of a very original and unique settlement. From a current perspective, the essential moments of Vilijampolė district development can be seen.

Attention should be drawn to the period of Vilijampolė development in the first half of the 17th century, when the advancement of Kaunas reached the highest point of the entire feudal period, because it was a city of rich merchants and craftsmen, not feudal lords. At that time, 15 thousand people lived in the city. Unfortunately, before the war of 1655–1660, a fire occurred here, and after the Swedes occupied Kaunas, it was destroyed, robbed and deteriorated by the black death. In 1667–1673, in the city of Kaunas, only about 4500 inhabitants could live [15], while Vilijampolė, the build-up of which was launched by the Radvilos, was an attractive place to live for people who returned from war but were not able to live in the post-war, destroyed Kaunas. Although it was the time of great economic and political upheaval in Lithuania-Poland Commonwealth, and Kaunas was heavily destroyed, yet, these conditions caused prompter evolution of suburbs that did not belong to city’s jurisdiction, and Vilijampolė became a great trading rival of Kaunas.

Undoubtedly, the growth of the settlement was influenced by the prohibition for Jews to be engaged in activity in Kaunas since 1682, therefore, Jewish people moved to Vilijampolė. Vilijampolė history of 17th century determined the ethnic composition of this settlement, as well as the economic and cultural growth. In the 13th century, Vilijampolė was even called a town of Jews. The dwelling spaces of Jews were limited to residential houses and a complex of structures, related to religion ceremonies (a synagogue, a sauna with a ritual pool (mikva), ritual slaughterhouse, a morgue).[16]

In 1882, Rabbi Note Hirsh Finkel established a seminary for rabbis and lower rank Jewish spiritual leaders in Vilijampolė, which was called Yeshiva of Slabada. Yeshiva of Slabada, or in other words “Kneset–Israel” (Israeli meeting). This fact should be mentioned as an important one, because this Yeshiva was one of the most prominent rabbi schools in Europe in 19th century, which demonstrates the status and thriving of Jewish community in Vilijampolė at that time. Namely for these reasons, this town used to be a strong trading unit, which had a very clear ethnic composition. Jews from Vilijampolė were a very closed community, which had created sufficiently dynamic ties with Kaunas, seeking economic well-being. Trading was thriving in the district, timber rafting station was operating, while in the 20th century, such objects like Volfas Engelman brewery, factory of matches “Etna” owned by brothers Finkenstein and Sargėnai brick factory, built in 1899, were opened. These industrial objects were quite large at that time and very important to expansion of industry.

The Golden Era of Vilijampolė

The second phase of evolution started after World War I with Vilijampolė connected to the city of Kaunas. All land plots became state-owned and a new growth phase of Vilijampolė as part of the city started. There were favourable conditions in the suburb for industry development, and it started to expand promptly. In 1923, the number of local inhabitants was 6600, while in 1940, the number of district residents reached 18 thousand. Urban development of the district was closely linked with the economic and cultural changes, and in 1924, a new bus line Railway Station – Vilijampolė was opened [17]. The district was connected to the city, the company “Auto”, which in that year opened a bus line from Rotušė [Town Hall] to Panemunė, gave the start to bus traffic. In 1914–1915, pontoon bridges were built over the Nemunas river near current Lampėdžiai and over the Neris to Vilijampolė near Kleboniškis and the Old Town. (see Fig. 8). Vilijampolė not only formally became part of Kaunas, but physically also integrated itself into a new urban formation. Interwar Vilijampolė had an identity and a precisely formulated task “to concentrate the industrial district” in the Provisional capital. Vilijampolė and surrounding districts expanded successfully and were gradually reorganized, so that they would become part of Kaunas city naturally: “it is intended in Vilijampolė to establish a trade port and concentrate an industrial district. Therefore, sooner or later it would be necessary to include Vilijampolė into the railway network.”[18]

After connecting to the city, the important industrial buildings used to be erected promptly even before the War, the majority of them influenced greatly the growth of the entire Vilijampolė district, while some economic activity of several enterprises continued for a long time after World War II, or even has been executed so far. It’s worth mentioning that in 1930, a land plot of 5 ha was assigned to Veterinary Academy.[19] This structure of new architectural quality built in the district, as well as an object of academic significance, was a great event in new part of the city. The architectural style of the ensemble embodied search for a new national style; the full complex was completed in 1940.[20]

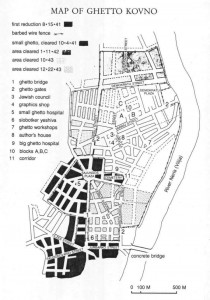

The golden era of Vilijampolė had come to an end almost without acceleration: from 1940, Vilijampolė lived one of the cruellest and most tragic periods in its history, and which undoubtedly interrupted progressive so far expansion of the settlement and pushed this district into urban stagnation, the consequences of which have been visible and liquidated so far. On June 15th 1940, the first Soviet occupation started and buildings of Vilijampolė offices and enterprises were nationalized. After one year exactly, on the 14-18 June 1941 [21] Soviet authorities organized mass deportation of Lithuania’s residents. On 25 June, after Kaunas city control has been taken over by German army and security police, persecution of Jews commenced. In the night from June 25th to June 26th, the pogrom took place in Vilijampolė that had been incited by Germans. 1500 persons of Jewish origin were killed. After the new occupying authority of Nazi came to power, a decree was issued forcing all Jews from Kaunas to move within the period 15 July to 15 August to Vilijampolė. On 29 October of that year, 9200 Jews from Vilijampolė were convoyed to the Ninth Fort, where they were shot to death on the same day. In September 1943, Kaunas Ghetto was transformed into a concentration camp (see Fig. 9, Fig. 10), while on 19 July 1944, the camp was liquidated, the prisoners transported to other German concentration camps. Probability of surviving the Kaunas Ghetto was extremely low, some 300–400 people remained alive from total 17 thousand. [18] The retreating Germans set to fire the Northern part of Vilijampolė, the remained part of Vilijampolė residents fled to the West as they feared the new Soviet occupation, following in August. In the war time, about 60% of Kaunas industrial enterprises were destroyed [23], bridges and some public buildings were blown up, and then the great flood of 1946 followed, which brought destruction to many homesteads on the banks of the rivers Nemunas and Neris.

World War II and partial deterioration of the Slabada took place exactly during the very beginning of adaptation of Vilijampolė as the district, which had been interrupted and potentially has never been completed. The major urban problem, which remained after Kaunas Ghetto liquidation in 1944, was not a deteriorated or destroyed district of a city, but a town, a village or a settlement, surrounded with a territory of another city, yet, destroyed.

After the war, Vilijampolė became a nominal space of the city, not performing in full general functions of a city and losing the character of an independent settlement, which had not integrated itself into the new ecosystem of Kaunas city. It became a suburb, surrounded by the city. A half of the century has elapsed from those events, and again historical discourse has changed, yet, the status of a small and closed community mentality is felt as well as the provincial existence of small district. It can be noticed, because a network of small residential areas is prevailing in the district with the objects meeting just local needs. In the old part of this area, no large or extremely important objects or public spaces exist performing a general function of a city.

“Sąjungos” Square

In the territory of the present “Sąjungos” Square, by the end of the 19th century (exact date not known), a catholic cemetery was established. This territory was linked to the fact of connecting with Kaunas city in 1919, because Vilijampolė district planning was launched in the jurisdiction of Kaunas city planning and development. In 1929, the project of Vilijampolė suburb plan was drawn up by the civil engineering specialist and architect, well known in Kaunas at that time, Edmund Fryk [24], a circular shape Sąjungos Square was planned between Panerių and Linkuvos streets. From this square, it was planned to lead another five additional streets. Meanwhile, in the existing territory, three closed blocks were planned very rationally, with boundaries made by transverse and longitudinal streets.

Fig. 12. The plan of the Sąjungos Square in 1935.

Fig. 12. The plan of the Sąjungos Square in 1935.

A situation occurred that this residential district had no space for a park. Although at first sight, the bank of the river Neris would be an ideal variant for an urban type park, nevertheless, this idea was rejected soon. Taking into consideration frequent and considerable floods on the riverside of the Neris, the Park would be deteriorated during each dangerous thaw in the spring. The Measurement Division of the Municipality proposed three real variants:

“1. To landscape and plant the plot, reserved by Land Reform Commission next to the cemetery of Vilijampolė, as the cemetery would be removed (see Fig.11; Fig. 11.1)

2. To assign for the Park the plot already commenced and plant with greenery the side of Sąjungos Square, which does not contain buildings. (see Fig. 12)

3. If these plots are not sufficient, to ask the Land Reform Commission (in the case of winning the lawsuit) to assign the plot, which has not been parcelled yet.”[25]

The Chief Inspector of Construction and Land Routes approved the project of Vilijampolė Park and “Sąjungos” Square on the 16 October 1936. [26] According to this project, the Park had been planned between “Sąjungos” Square, Brolių, Puodžių and Skirgailos streets – i.e., in the centre of today’s square.

No project was launched as World War II started. The occupations imposed by the Soviet Army and Nazi Germany had not left any possibility to continue planned development of Vilijampolė. After Kaunas Ghetto became a concentration camp in 1943, “Sąjungos” Square territory played a role of a centre, around which barbed wire fences divided the camp into separate territories. Neither cemetery area, nor the church under construction fall behind the fence, and these objects played a role of a corridor between the territories of the camp. The cemetery was removed in the middle of the eighth decade, part of it could be destroyed. The relatives themselves had to take care of removing the remains. According to the people who remember cemetery removal, not all residents knew in advance about the removal of remains, hence, not all were in time to remove. This reason implies that, although officially the cemetery does not exist anymore, still, under the ruins of former Monument, there are remains of people, who had been buried there.

The Monument to the Communist Youth League Members

In 1974, a Monument to the Communist League Members, who Lost their Lives for Soviet Government was launched. The Monument was created in memory to the 60th anniversary of the first congress of Communist Youth League in Lithuania, the authors of the memorial ensemble were architects Gediminas Baravykas, Vytautas Vėlius and sculptor Steponas Šarapovas. The ensemble consisted of three roads, to be more exact, three concrete corridors, which directed the viewer to the site on the top of an elevation. After the visitors have reached the site, they could see a sight with two figurative bass-reliefs: “Priesaika” [The Oath] (see Fig. 13.), devoted to the establishment of Communist Youth League in Lithuania, and “Kova” [The Fight], devoted to underground members of the Communist Youth League, who were operating during the war.[27] The centre of the Memorial was the altar, „incorporated“ into the intersection of roads (see Fig. 14) with the inscription: “To Communist Youth League members, who Lost their Lives for Soviet Government in 1941-1945”. This work was uncovered on 25 January 1975 by the Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania.[28] The project was time-consuming, Šarapovas was named winner of the contest in 1965, while the erection was launched even in 1974.[29] At that time, the press wrote that estimated value of the Monument was 342 thousand rubbles.[30] (see Fig. 15, Fig. 16)

The purpose of the Monument raises extremely strong doubts, it is similar by its topics to a political work of a declarative character. By this work they appeal to a fragment of Vilijampolė history, when, within the period 1919–1940, in Vilijampolė the communist underground was operating with a secret printing house, underground apartments and anti-state meetings, explosive hideouts, anti-fascist combat organization, established in 1942.[31] Still, this is a more local history episode, its immortalization is without a clear artistic motivation for creation of

such a scope monument in this particular place. In 1942, in the Ghetto, all communist and anti-fascist circles teamed up into an anti-fascist combat organization, consisting of 500 members, among them were 21 communists and 50 Communist Youth League members.[32] The monument extremely brutally ignored the ethnic genocide of another almost 17 thousand people, the people who could not be assigned to Communist Youth League members or Bolshevik residents. The Holocaust was treated as mass killings of “Soviet citizens”, not naming the nationality of the victims.[33] Discussing the artistic form of “Sąjungos” Square expression, it was noticed that the work was a valuable one due to contribution of the authors to Lithuanian modernistic architecture and sculpture (see Fig. 17). This work clearly demonstrates the artistic style of both Baravykas and Šarapovas still, currently, there is no integrity of this work.

On the 28 November 1991 [34], the bronze bass-reliefs were dismantled and transported to Grūtas Park, the condition of structure concrete paving and the square itself is bad, ground formation practice itself currently does not create any quality space. Former artistic values in today’s context are illegible and do not have any emotional impact. The topic of the Monument was nominal as well, even its name “Sąjungos” [Union’s] is misleading, because it does not perform functions of a “square”, a local square at best. The “square” itself with the steles or without steles do not pretend to the status of a public space. This territory remains that of the district, but not a public space. Around the hill, a poor image of this part of the city is formed, which does harm to the micro-district.

The Vision of “Sąjungos” Square Regeneration

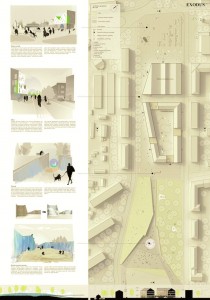

The fate of “Sąjungos” Square has not been identified so far, still some hopes appeared when on 20 September 2014, a simplified architectural-urban open tendering procedure to design the vision of “Sąjungos” Square in Kaunas was announced This competition was organized by Kaunas Branch of Lithuanian Association of Architects, while the aim of it was to find an optimal proposal concerning the strategy of urban and architectural formation of “Sąjungos” Square and adjacent territories. On the 17 November, the commission of Kaunas Architecture and Urbanism Expert Panel received 6 works for competition, while later, we became aware of 27 teams, which retrieved from the online database the terms and conditions of the competition.[35] Two prevailing positions stood out when reviewing the proposals submitted: two designs with an urban built-up and four proposals with park regeneration ideas. I, myself, alongside with architects Matas Šiupšinskas and Dominykas Kalmatavičius participated in this competition as well, our team submitted “Exodus” design.

The commissions awarded the first place to our project “Exodus” (see Fig. 18, Fig. 19). In the opinion of the panel, this work responded the best the tasks set in the tendering procedure programme: historic material has been taken into consideration, as well as the structure of blocks, a traditional scale of a square in Kaunas city. Namely this award confirms once again that solution to problems is linked to the survey of the place and historic context analysis. Using the information collected, a conclusion has been drawn that, if a space is divided into smaller segments, it is easier to control it. Sculpture and other elements of design must create characters of separate, smaller segments and form different needs of the city and local community, reflecting their different functions. Taking into consideration the history of the district’s expansion and current activity here, it is recommended to develop the character of small businesses and craftsmen community here, treat “Sąjungos” Square as a symbolic centre of it and permit its partial build-up.

It is proposed to apply stricter functional zoning in the project and form two separate public spaces: to separate the city square at the Linkuvos and Panerių street junction and create a local square of community in the territory of former memorial (see Fig. 20). In order to form clearly the boundaries of these spaces in the territory, it is proposed to move the park part of the Square to the riverside, while in the former place to form a new build-up (see Fig. 21). The division of the Square from one nominal space into two parts alongside with stricter zoning would enable public spaces around to concentrate themselves to different functional programmes and businesses. After huge nominal spaces (ankers) have been created in the territory, the attachment occurred between those spaces would promote more active circulation of flows in the surrounding territory. The junction between Linkuvos and Panerių streets is good to form the space of urban character, which is able to accommodate cultural and commercial activity (see Fig. 22). It is proposed to develop commercial activity in the territory of the Square, to find a form for sculpture elements as well, which should supplement the character of the district, engaged in trading and crafts.

In the former space of the Monument, the parallel narratives disclosed could be developed (cemetery of Christians, Jewish Ghetto territory, Soviet period scars). This territory could be adapted for free time of local residents, preserving the existing hill, to which all local dwellers are emotionally attached. The formation of recreational zones on the territory of former cemeteries is a practice frequently met in Europe – City Garden in Kaunas and Ramybės [Peace] Park are well known examples. Having analysed the possibilities of renovation of this place, it is proposed to flood with running water the bearing walls of the Monument remained, thus transforming static walls into murmuring waterfalls. This creative work should articulate a new emotional message and create allusion to the divided sea to the viewer. The paths and street furniture appeared on the slopes would invite to use actively the summit of the hill and overview from above the amphitheatre designed in the Monument (see Fig. 23).

In my vision, this place of the community’s square would be a perfect place to immortalize the historic developments of the district and this way celebrate the centenary of joining Kaunas in 2019. Finance sources could be not only European Union funds, but also income, received for long-term renting of land plots in the territory. I propose moving the park part of the Square to the riverside of the Neris, create infrastructure, attracting residents of the district. Bicycle and pedestrian paths would divide the space into the strips of different activity and character, create a valley on the bank, which would allow a more convenient access to the water, which is the opinion, most often expressed by Kaunas people today.

Sąjungos Square, Relationship between the Community and the Place since 1991

After the bronze bas-reliefs had been dismantled from the place intended, concrete walls remained not functioning alongside with dolomite tiles. After the earth graphics example of impressive height has started its existence without any message being transmitted, it became a physically dangerous space, generating bad morale. The dwindling composition of concrete tiles and the hill as if tells passers-by that this is a no-man’s land. A huge paved territory is not the best example of a symbol, defining activity of the community. The space, formed spontaneously, not illuminated at night, with limited visibility from surrounding buildings is unsafe. An image of poor part of the city is formed around the hill, which does harm to the micro-district.

In 2004, city’s periodicals mentioned a fact of sculpture plein air that took place in this territory namely. Those had been the first initiatives which in one way or another had been intended for transformation of the space of this place towards existence of higher quality. Local community was dissatisfied with the parts of the Memorial and park, as nothing had been put in order. Just interview with Vilijampolė elder Gintautas Sinkevičius provided positive emotions in the article. It was mentioned there that, as the project did not need funding from the city’s budget, the eldership was able on its own to find sponsors to make sculptures. On the one hand, one could be pleased that Vilijampolė community had become responsible for its own environment and took initiative. Still, in the larger fabric of the city, at the municipality there was no decision made in 2004. The space has not been given any scenario of a common space of the city, this Square has remained to be solved on the local level. During the plein air, three sculptures were created: Danielius Sodeika‘s “Dviratis” [A Bicycle], Algimantas Šlapikas‘s “Durys”[The Doors] and Simonas Šidlauskas‘s “Svarstyklės” [The Scales].[37] Metal work compositions after three weeks elapsed became vandalized by local hooligans. On 20 October 2004, the newspaper “Lietuvos Aidas” wrote about the vandalized sculpture of the bicycle, it expressed regrets that there are people who obstruct the idea of reviving the image of the Square.[38] Today none of these sculptures has survived. This example told in the press shows perfectly well that street design solutions or a decorative park sculpture does not change the situation, it does not regenerate the space. Through public space conversion, the issues of local problematics must be clearly arisen, a long-term vision of conversion of the place must be created and only then particular objects or artistic works designed.

On the 21 May 2014 [39] at Kaunas branch of the Association of Lithuanian Architects an expanded discussion of Kaunas Architecture and Urbanism Expert Council took place on possibilities to organize a tendering procedure to create urban and architectural vision of Sąjungos Square. At the beginning of the discussion, it became known that Vilijampolė community is interested in the issue of Sąjungos Square as well. The members of Vilijampolė Community Centre “Varšva” have their own attitude and their own proposal on Square regeneration issue. Undoubtedly, it is good to know that local community is interested and active as far as this issue is concerned, still, their own concept is not a serious, reasoned proposal. The community proposed in the territory of the former Monument to establish a Centre of Entertainment and Education „Žaidimų akademija”,[40] expose temporary sculptures and installations in the territory of Square. The proposal is not far-sighted, because it is based on a method already tested and unsuccessful to erect park-type sculptures in a square, hoping for qualitative changes, caused by design solutions. „Žaidimų akademija”, as an organization in reality does not seem to be a real possibility, as a question arises, whether there is demand for such facility on the Centre’s side and how it is going to survive and who would be responsible for it.

On 26 November 2016, I myself participated in the meeting with the local community to discuss the project of Square regeneration. The meeting was organized by Vytautas Magnus University second year Creative Industries Master’s programme students. To participate in the meeting, active members of local community, the elder of the community, several politicians of Kaunas city, representing interests of Vilijampolė people, had been invited, as well as a co-author of the “Exodus” project, i.e., myself. During this meeting, the students of Creative Industries were leading a discussion of free format, devoted to the future and landscaping of Sąjungos Square. Local community members were asked about their wishes and expectations, their relationship to this place and how they evaluated the current situation. I, in turn, shared my insights, gained through experiences and competencies while participating in the tendering procedure for regenerating this space, because to this place I have devoted several years of my attention as a professional.

Admittedly, the result I had expected was opposite and quite a paradox one. Although all members of the community expressed their wish to see how in the future Sąjungos Square will become a quality, regenerated space, yet they opposed any urban or architectural intervention. Due to some reasons but mostly due to a lack of knowledge in this sphere and reluctance to go deeper into substantial problems of this place, part of local residents demonstrated that landscaping of the Square means renewal of welfare elements. In their opinion, replacement of benches, paving and bins for public use is the main measure for qualitative change of the space.

Paradoxically, in 2014, the members of Vilijampolė Community Centre “Varšva” formulated the needs, highlighting that “Žaidimų akademija” [Academy of Game] is necessary, in other words they needed premises or a building, yet in 2016, the same people strictly opposed any scenario of the territory build-up. This way a need is formulated, which is impossible to realize under given conditions. Such a situation illustrates that a delicate and time-consuming process may be awaiting if you want to involve local community into these processes. Education and mutual listening are necessary in this case.

In 2017, during Kaunas Biennale, this space drew attention from guests from abroad as well. In Sąjungos Square, large format photographs were exposed to actualize the reworked memory, the subjects of city and time. This installation was created by artists from Germany, Horst Hoheisel and Andreas Knitz. In my opinion, such campaigns are important and useful when you look at the overall process of place transformation, still, do not be deceived: these works invite to some discussion, they do not transform the space qualitatively.

To sum up my own experiences with Sąjungos Square, I can tell just this: I hope that the word will be embodied. When will these insights and information be useful and serve for regenerating this space into a place of quality meeting today’s needs? This is not just a testing, it is a perfect opportunity to create a unique and quality public space, standing out by its design and not only, but by a unique character of this place. The spirit of Vilijampolė, a small trading town, has been viable so far and this is a key which must assist in regenerating this space.

References

[1] Miestų viešosios erdvės: Kūrybiškumas ir meninė intervencija [Public Spaces of the Cities: Creativity and Artistic Intervention] sudarė Raimonda Laužikienė, Klaipėda: Všį Klaipėdos ekonominės plėtros agentūra, 2009, p.24.

[2] Elona Lubytė, „Menas viešosiose miesto erdvėse: Kūrėjo, užsakovo ir publikos vertybių sandraugos klausimas” [Art in the Public Spaces of a City: The Issue of Community of a Creator, Customer and Public Values], in: Urbanistika ir architektūra, Vilnius, 2011, Nr. 35(1), p. 38–50.

[3] Audrius Novickas, Atminties prasminimas miesto aikštėje: Nuo paminklo iki patirčių erdvės [Turning Memory Meaningful in a Square of a City: from Monuments to the Space of Experiences], Vilnius: Technika, 2010, p. 13.

[4] Louis G. Redstone, R. Ruth Redstone, Public Art: New Directions, New York: McGraw – Hill Inc., 1981, p. 5.

[5] Audrius Novickas, op. cit., p. 13.

[6] Ibid, p. 27.

[7] Elona Lubytė, op. cit., p. 44.

[8] Umberto Eco, Atviras kūrinys [The Open Work], Vilnius: Tyto Alba, 2004, p. 41.

[9] Louis G. Redstone, Ruth R. Redstone, op. cit., p. 4.

[10] Tomas S. Butkus, Miestas kaip vykis: Urbanistinė kultūrinių funkcijų studija [A City as an Event: An Urban Study on Cultural Functions], Kaunas: Kitos knygos, 2011, p. 69.

[11] Matthew Carmona, Tim Heath, Toner Oc, Steven Tiesdell, Public Places – Urban Spaces, London: Architectural Press, 2003, p. 54.

[12] Alvydas Butkus, „Kauno vietovardžiai: Vilijampolė“ [Kaunas Place Names: Vilijampolė], in: Kauno diena. 1998 m. sausio 17, p. 26.

[13] Algimantas Miškinis, „Vilijampolės būta savarankiško miesto” [Vilijampolė Used to Be an Independent Town], in: Statyba ir architektūra, 1973, Nr. 3, p. 30–31.

[14] Raimundas Kaminskas, Vilijampolės metraštis: faktai, įvykiai ir žmonės [Vilijampolė Chronicle: Facts, Events and People]. Kaunas: Kitos spalvos, 2012, p. 3.

[15] Ibid., p. 6.

[16] Rasa Račiūnaitė, Lietuvių šeima vertybių sankirtoje (XX a. – XXI a. Pradžia [A Lithuanian Family at the Turn of Values (20th century – the begining of the 21st century)], Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo universiteto leidykla, 2012, p. 50.

[17] Raimundas Kaminskas, Vilijampolės laiko žemėlapis [Vilijampolė Temporal Map], [interactive], 13 November 2009 , [accessed 01 February 2015], http://www.xxiamzius.lt/numeriai/2009/11/13/aktu_01.html

[18] Rasa Račiūnaitė, op. cit. p. 59.

[19] Kauno architektūra [The Architecture of Kaunas], sudarytoja ir mokslinė redaktorė Algė Jankevičienė, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1991, p 59.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Arūnas Bubnys, Kauno getas 1941–1944 [Kaunas Ghetto 1941-1944], Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras, 2014, p. 29.

[22] Ibid., p. 16.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Danutė Rūkienė, Eugenijus Rūkas, „Buvusios Vilijampolės katalikų kapinės ir Šv. Juozapo bažnyčia” [Former Vilijampolė Catholic Cemetery and St. Joseph‘s Church], in: Istoriniai tyrimai: mašinraštis. Kaunas 1995, p. 5.

[25] Ibid.p. 6

[26] Ibid.

[27] Skulptūra 1975–1990 [Monuments and Statues in 1975-1990], sudarė Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, Elona Lubytė, Vilnius: Aidai, 1997, p. 41.

[28] M. Tamašauskas, „Paminklas komjaunuoliams pogrindininkams” A Monument to Members of Communist Youth League – Underground Organization Members ][, in: Komjaunimo tiesa, 1974-08-30. p. 8.

[29] „Narsiųjų kovotojų atminimui”[ In Memory of the Brave Fighters] , in: Tiesa, 1979-01-27, p.12.

[30] E. Skarelis, „Atminimas kritusiems komjaunuoliams”[ In Memory to the Communist Youth League Members, who Lost their Lives], in: Kauno tiesa, 1975-01-29.

[31] Arūnas Bubnys, op. cit., 120.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Arūnas Dambrauskas, „Rekviem bronziniams komjaunuoliams” [Requiem to Bronze Communist Youth League Members], in: Kauno tiesa, 1991-11-29, p. 7.

[35] Lietuvos architektų sąjungos Kauno skyrius, Sąjungos aikštės vizijos urbanistinio architektūrinio supaprastinto atviro projekto konkurso negalutiniai rezultatai [Kaunas Branch of Lithuanian Union of Architects, Provisional Results of Open Tendering Procedure for Design of Urban and Architectural Vision of Sąjungos Square], [interactive], [accessed 01 February 2015], http://laskaunas.lt/konkursai/sajungos-aikstes-vizijos-urbanistinio-architekturinio-supaprastinto-atviro-projekto- konkurso-negalutiniai-rezultatai/

[36] Rasa Masiokaitė, „Spalvingos skulptūros iš Sąjungos aikštės išvaiko nuobodulį”[ Colourful Sculptures Take Away the Boredom from Sąjungos Square], in: Laikinoji sostinė, 2004-10-07, p. 12.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Iveta Skliutaitė, „Vandalų nuniokota skulptūra vėl džiugina akį”[ The Vandalized Sculpture Pleases the Eye again], in: Laikinoji sostinė, 2004, p. 8.

[39] Sąjungos aikštės vizijos urbanistinio architektūrinio supaprastinto atviro projekto konkurso negalutiniai rezultatai [Kaunas Branch of Lithuanian Union of Architects, Provisional Results of Open Tendering Procedure for Design of Urban and Architectural Vision of Sąjungos Square] , op. cit.

[40] Lietuvos architektų sąjungos Kauno skyrius, Vilijampolės bendruomenės centras pristato savo Sąjungos aikštės vizijas, [Kaunas Branch of Lithuanian Union of Architects, Vilijampolė Community Centre Present their Visions of Sąjungos Square] [interactive], [accessed 01 February 2015], http://www.laskaunas.lt/las-ks-naujienos/vilijampoles- bendruomenes-centras-pristato-savo-sajungos-aikstes-vizijas/.

Literature

1. Bubnys Arūnas, Kauno getas 1941–1944 [Kaunas Ghetto in 1941-1944], Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras, 2014, p. 29.

2. Butkus Alvydas, „Kauno vietovardžiai: Vilijampolė“[Kaunas Place Names: Vilijampolė] , in: Kauno diena. 1998 m. sausio 17, p. 26.

3. Butkus Tomas S., Miestas kaip vykis: Urbanistinė kultūrinių funkcijų studija[ A City as an Event: An Urban Study on Cultural Functions] , Kaunas: Kitos knygos, 2011.

4. Carmona Matthew, Heath Tim, Oc Toner, Tiesdell Steven, Public Places – Urban Spaces, London: Architectural Press, 2003.

5. Dambrauskas Arūnas, „Rekviem bronziniams komjaunuoliams” [Requiem to Bronze Communist Youth League Members], in: Kauno tiesa, 1991-11-29, p. 7.

6. Eco Umberto, Atviras kūrinys[The Open Work], Vilnius: Tyto Alba, 2004.

7. Kaminskas Raimundas, Vilijampolės laiko žemėlapis [Vilijampolė Temporal Map], [interactive], 13 November 2009, [accessed 01 February 2015], http://www.xxiamzius.lt/numeriai/2009/11/13/aktu_01.html

8. Kaminskas Raimundas, Vilijampolės metraštis: faktai, įvykiai ir žmonės [Vilijampolė Chronicle: Facts, Events and People. Kaunas: Different Colours], 2012.

9. Kauno architektūra [The Architecture of Kaunas], sudarytoja ir mokslinė redaktorė Algė Jankevičienė, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1991.

10. Lietuvos architektų sąjungos Kauno skyrius, Sąjungos aikštės vizijos urbanistinio architektūrinio supaprastinto atviro projekto konkurso negalutiniai rezultatai Kaunas Branch of Lithuanian Union of Architects, Provisional Results of Open Tendering Procedure for Design of Urban and Architectural Vision of Sąjungos Square] [interactive], [accessed 01 February 2015], http://laskaunas.lt/konkursai/sajungos-aikstes-vizijos-urbanistinio-architekturinio-supaprastinto-atviro-projekto- konkurso-negalutiniai-rezultatai/

11. Lietuvos architektų sąjungos Kauno skyrius, Vilijampolės bendruomenės centras pristato savo Sąjungos aikštės vizijas ,[Kaunas Branch of Lithuanian Union of Architects, Vilijampolė Community Centre Present their Visions of Sąjungos Square] [interactive], [accessed 01 February 2015], http://www.laskaunas.lt/las-ks-naujienos/vilijampoles- bendruomenes-centras-pristato-savo-sajungos-aikstes-vizijas/.

12. Lubytė Elona, „Menas viešosiose miesto erdvėse: Kūrėjo, užsakovo ir publikos vertybių sandraugos klausimas” [Art in the Public Spaces of a City: The Issue of Community of a Creator, Customer and Public Values] , in: Urbanistika ir architekt ra, Vilnius, 2011, Nr. 35(1), p. 38–50.

13. Masiokaitė Rasa, „Spalvingos skulptūros iš Sąjungos aikštės išvaiko nuobodulį”[Colourful Sculptures take Away the Boredom from Sąjungos Square] in: Laikinoji sostinė, 2004-10-07, p. 12.

14. Miestų viešosios erdvės: Kūrybiškumas ir meninė intervencija [Public Spaces of the Cities: Creativity and Artistic Intervention], sudarė Raimonda Laužikienė, Klaipėda: Všį Klaipėdos ekonominės plėtros agentūra, 2009.

15. Miškinis Algimantas, „Vilijampolės būta savarankiško miesto”[Vilijampolė Used to Be an Independent Town], in: Statyba ir architektūra, 1973, Nr. 3, p. 30–31.

16. „Narsiųjų kovotojų atminimui” [In Memory of the Brave Fighters], in: Tiesa, 1979-01-27, p.12.

17. Novickas Audrius, Atminties prasminimas miesto aikštėje: Nuo paminklo iki patirčių erdvės, [Turning Memory Meaningful in a Square of a City: from Monuments to the Space of Experiences] Vilnius: Technika, 2010.

18. Račiūnaitė Rasa, Lietuvių šeima vertybių sankirtoje (XX a. – XXI a. Pradžia) [A Lithuanian Family at the Turn of Values (20th century – the begining of the 21st century)], Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo universiteto leidykla, 2012.

19. Redstone Louis G., Redstone Ruth R., Public Art: New Directions, New York: McGraw – Hill Inc., 1981.

20. Rūkienė Danutė, Rūkas Eugenijus „Buvusios Vilijampolės katalikų kapinės ir Šv. Juozapo bažnyčia”[Former Vilijampolė Catholic Cemetery and St. Joseph Church], in: Istoriniai tyrimai: mašinraštis. Kaunas 1995, p. 5.

21. Skulptūra 1975–1990 [Monuments and Statues in 1975-1990], sudarė Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, Elona Lubytė, Vilnius: Aidai, 1997.

22. Skarelis E., „Atminimas kritusiems komjaunuoliams”[In Memory to the Communist Youth League Members, who Lost their Lives], Kauno tiesa, 1975-01-29.

23. Skliutaitė Iveta, „Vandalų nuniokota skulptūra vėl džiugina akį” [The Vandalized Sculpture Pleases the Eye again] , in: Laikinoji sostinė, 2004, p. 8.

24. Tamašauskas M., „Paminklas komjaunuoliams pogrindininkams” [A Monument to Members of Communist Youth League – Underground Organization Members] , in: Komjaunimo tiesa, 1974-08-30. p. 8.